Change is easy. Navigating the many transitions of the change is not. Change is easy. Navigating the many transitions of the change is not.

10/23/2022, 12:45 p.m. CST

Read Time: 2 min. 30 sec. In the book Managing transitions: Making the most of change, written by William Bridges, leaders learn how change is easy, and transitions within the change are complex. The author describes that transitions are psychological and include a "three-phase process that people go through as they internalize and come to terms with the details of the new situation that the change brings about" (page 21 of 256). A transition consists of the ending (losing, letting go), the neutral zone, and the new beginning. In the ending, people have the challenge of letting go. Here, people must let go of things and behaviors that make up their identity. This is when leaders need to help their colleagues deal with their losses.

After the ending, we enter an uncertain time called the neutral zone. This is an odd place to find yourself. The old is not entirely gone, yet the new is unknown and chaotic, scary, and not fully operational. The neutral zone is an excellent time for creativity and innovation and a time for stress and anxiety. There is a lot of potential for growth in this stage. After surviving the stress of this transition, we enter a new beginning. In the new beginning, a new identity develops in people, new energy abounds, and people come to work with a new sense of purpose that makes the change work.

Patrick Lencioni reminds us that even positive change comes with loss and emphasizes the importance of a ceremony for the ending to move forward. It is about saying "goodbye" to the past while simultaneously burning your ship.

When discussing the neutral zone, Lencioni compares it to buyer's remorse. For example, you might be in a new job, wonder if you made the right decision, and debate about leaving it early on. Here, we remind ourselves of the loss and recognize that we control our response. As leaders, we must have astute situational awareness and deliver support to colleagues for their loss. If we do not offer support, people will return to the old way, give up, or quit and stay, leading to bitterness. We help others get through the neutral zone by showing up, being present, telling the truth, and letting go of the outcomes. And we do this through care and concern. This is when we try to reassure that it will be okay and the challenge is not attempting to solve the problem for someone else. Some examples to help teachers who are in the neutral zone are: include providing time and training, providing factual information, offering teachers roles to participate in, and offering time for teachers to discuss and reflect with leaders.

Change is easy. Navigating the many transitions of the change is not. People must be constantly reminded of four programmatic and specific things when going through a change: purpose, picture, plan, and part. It is essential to continually remind people why (purpose) they are going through the change in the first place. Second, painting a picture of the destination of where we are going and why it will be better. Third, have a plan delivered in small, understandable, and doable chunks for the change, and, finally, people will need to know their part, or role, in the transition. Change is external and usually welcomed once it is over. The multiple internal transitions within the change often make it hard. As leaders, it is our responsibility to help everyone through the change. This means supporting people through the multiple internal transitions that often make change hard. We must be there for our colleagues, answer their questions, and help them understand what is happening. Only by working together can we successfully navigate through times of change and come out stronger on the other side.

References:

0 Comments

10/9/2022, 11:35 a.m. CST Read Time: 2 min. 33 sec. Last week we were introduced to the ladder of inference. The ladder of inference is a mental model that helps us understand how we come to the conclusions we make. It starts with the data we take in from our senses (what we see, hear, etc.). From there, we add our own interpretation to the data. Finally, we come to a conclusion and take action based on that conclusion. When used correctly, the ladder can save you from the proverbial foot-in-the-mouth. This is done by thinking more with facts and not automatically jumping to conclusions. Ultimately, the ladder can help you explain your thinking and reasoning to others. Thinking and explaining your thinking to someone isn't always the easiest. Sometimes we clam up, get defensive, or avoid the situation altogether, which drowns any potential for collaboration—knowing how and when to collegially say what you're thinking is done through a balance of advocacy (stating our views) and inquiry (asking questions). We must know when it is the right time to state our views and ask questions; context is critical. Pushing out emergency information would not be a time for inquiry. However, having a planning meeting and leaving with a plan for communicating emergency information would include a healthy combination of advocacy and inquiry. Below are a few protocols and prompts written by Senge et al. (2012) that help facilitate advocacy and inquiry with some pointers on what to say when you get stuck in a situation (pp. 104-107). To help with advocacy (stating your views):

To help with inquiry (asking questions to reveal thinking in others):

When you are stuck in a disagreement:

When you are at an impasse:

In any situation, we must be aware of our biases and assumptions. We all tend to jump to conclusions, which can lead to conflict and misunderstanding. Recall the ladder of inference is a model to help us slow down our jumping to conclusions. The best way to avoid conflict and misunderstanding while building diverse perspectives is to practice a balance of advocacy and inquiry. Inquiry involves asking questions and genuinely listening to the answers. Advocacy is about sharing our views in a way that invites dialogue and debate. Combining these two approaches creates an environment where different perspectives can be heard and respected. This, in turn, leads to greater collaboration and understanding. So, the next time you find yourself in a disagreement, remember the importance of advocacy and inquiry. It may just be the key to finding common ground. See this short article from the Systems Thinker to learn more about how to have productive conversations. References:

10/2/2022, 12:50 CST Read Time: 2 min. 31 sec. Can 1+1=3? Have you experienced a situation with multiple people, yet everyone remembers it differently? Even better, someone looked at you wrong, not realizing they were making a face at the person behind you? As Kramer and Newman unpack the events of June 14th, 1987, Keith Hernandez remembered it differently. As a teacher, you are constantly making decisions based on the information you have. Sometimes, these decisions are small, like what to do when a student breaks a rule. Other times, they are much larger, like whether or not to recommend a student for expulsion. Regardless of the size of the decision, you always want to be sure that you are basing your decisions on accurate information. The ladder of inference is a cognitive model that helps us understand how we come to the conclusions we make. It starts with the data we take in from our senses (what we see, hear, etc.). From there, we add our own interpretation to the data. We might make assumptions based on our experiences or form judgments about what we think is right or wrong. All of this happens very quickly and often without us even realizing it! Finally, we come to a conclusion and take action based on that conclusion.The ladder comprises six "rungs" and sits on top of observable data and experiences. Starting from the top rung to the bottom rung:

As quirky as Kramer can be, he had a sense of inquiry and asked Hernandez "who did it" since he denied doing it. When doing this, Kramer came down the ladder. At this point, Kramer, Newman, and Hernandez recall the event. Still, while talking, Kramer and Newman quickly realize that Hernandez saw what happened differently. And come to find out, it was Roger McDowell (this is how 1+1=3)! In the end, Roger was talking and pointing right at Kramer and Newman (I'm guessing telling someone what happened to him during the game, my assumption rung of the ladder!). At the same time, Keith yells at Kramer to get out of the way, but it is too late! And to come down even more on the ladder, Jerry asks Keith, "why?" and then the real answer comes out. Kramer admits how he and Newman were picking on McDowell in the bullpen during the game. Did Kramer deserve what happened? Probably. Did he have the wrong guy? Absolutely. Based on their interpretation of an event, did Kramer and Newman hold onto misdirected anger towards Hernandez for far too long? You bet. The ladder of inference is a cognitive model that helps us understand how we come to the conclusions we make. It starts with the data we take in from our senses (what we see, hear, etc.). From there, we add our own interpretation to the data... Finally, we come to a conclusion and take action based on that conclusion. As teachers, we must be aware of this process and take steps to ensure that we base our decisions on accurate information. Watch the video below to learn more about the ladder of inference, and here is an article that helps explain this in more detail. References:

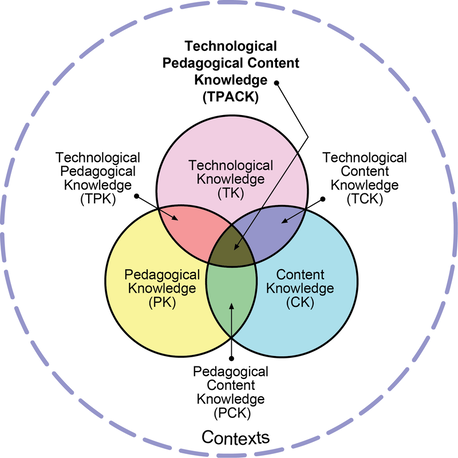

Technological frameworks assist educators with the effective integration of technology and teaching. TPACK applied through the design thinking process can assist teachers in developing students’ 21st-century competencies (Koh, Chai, Benjamin, & Hong, 2015). The intersections of TPACK are essential in teaching 21st-century competencies. Brown, Neal, and Fine (2011) reviewed how designing lessons with Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK) assist with the insertion of 21st-century thinking skills and sought connections between the two. This work indicated that the prevailing critical thinking instructional strategy needed to design effective lessons by preservice teachers was teacher questioning, inquiry-based learning strategies, open-ended questions, problem or project-based learning, and the use of PowerPoint for presentations. Teachers need to understand the content, including standards such as ISTE and competencies such as P21, and then transfer the content through proper pedagogical and technological applications. WHAT IS TPACK? Without the domains of TPACK, students may miss an opportunity to demonstrate their own understanding and application of learning. Silva (2009) stated that placing “an emphasis on what students can do with knowledge, rather than what units of knowledge they have, is the essence of 21st-century skills” (p. 630). As the educational landscape changes, technological tools, instructional strategies, and standards will come and go. Teachers who understand TPACK can leverage the complexities of mixing content, technology, and pedagogy and apply them in specific contexts leading to quality teaching (Mishra, Koehler, & Henriksen, 2011). TPACK was introduced to the educational field as a framework for integrating technology with content and pedagogy (Koehler et al., 2013). The TPACK framework recognizes the three bodies of teachers’ knowledge and the interactions among them described as CK (content knowledge), PK (pedagogical knowledge), and TK (technological knowledge; Koehler et al., 2013). CK is the teacher’s expert knowledge in the given subject area. It is referred to as “what” teachers teach, including a given discipline’s facts, concepts, and theories. CK implies that the teacher knows what and when to teach and is likely comfortable with content knowledge. (Common Sense Education, 2016; Crompton, 2016; Koehler et al., 2013). PK is how teachers teach while using their expert knowledge of the art and science of teaching. Teachers who are proficient in this body of knowledge know how to transfer knowledge using different assessments, instructional strategies, and learning theories. Being successful with the components of PK allows the teacher to create meaningful and relevant learning experiences for their students (Common Sense Education, 2016; Crompton, 2016; Koehler et al., 2013).  It is worth noting that people may have an abundance of technological knowledge. Still, they may not necessarily be able to apply it in the context of education. It is worth noting that people may have an abundance of technological knowledge. Still, they may not necessarily be able to apply it in the context of education. TK is the understanding of available technologies in teaching and learning. It represents teacher knowledge about the tools, including selecting, using, and integrating technology into the curriculum (Crompton, 2016). Koehler et al. (2013) stated that TK is more difficult to define than CK and PK because technology is ever-changing. Penning a definition of technology would be obsolete when the definition was published. Instead, Koehler et al. recommended defining TK with a definition proposed by the National Research Council Committee on Information Technology Literacy (1999), which defined fluency with information technology this way: "Persons understand information technology broadly enough to apply it productively at work and in their everyday lives, to recognize when information technology can assist or impede the achievement of a goal, and to continually adapt to changes in information technology" (p. 15). It is worth noting that people may have an abundance of technological knowledge. Still, they may not necessarily be able to apply it in the context of education. Technological knowledge does not imply focusing solely upon the hardware. Instead, it emphasizes the quality of the content available through digital resources (Crompton, 2016). At the intersections of CK, PK, and TK are the interactions of each body of knowledge: PCK (Pedagogical Content Knowledge), TCK (Technological Content Knowledge), TPK (Technological Pedagogical Knowledge), and TPACK (Technology, Pedagogy, and Content Knowledge). PCK occurs when Content and Pedagogical Knowledge are combined. When used effectively, PK and CK complement one another, allowing CK to transfer to the student as the CK and PK outcomes align (Common Sense Education, 2016; Crompton, 2016). DO YOU HAVE AN EXAMPLE? Using the example of teaching a student how to strike a golf ball may demonstrate a crude (nontechnological) PCK example. A CK outcome might be defined by explaining the elements necessary to hit a golf ball. By incorporating PK, the students can leverage a hands-on instructional strategy after the teacher models how to hold a golf club and demonstrate a proper backswing, impact position, and follow-through. CK, or the what, is transferred through the how, also known as PK (Common Sense Education, 2016; Crompton, 2016). For example, the student learns what a properly struck golf ball is and then transfers this content knowledge through the modeling and demonstrating of PK activities. The teacher can then follow with additional input and reinforcement, providing deeper learning and assessment opportunities for the original CK outcome. In this lesson, the student is engaged in a deep level of critical thinking for this knowledge and skill to transfer. Assessing critical thinking does not only apply to “school.” It applies to everyday life and issues significant to the community. Providing an opportunity for critical thinking in conjunction with real-world contexts makes learning relevant and is a recommendation of P21 (Dilley, Kaufman, Kennedy, & Plucker, 2015).  You can use technology to demonstrate student learning. You can use technology to demonstrate student learning. According to Koehler et al. (2013), TCK “is an understanding of the manner in which technology and content influence and constrain one another” (p. 16). Within TCK, teachers must master more than the content they teach; they must also understand how the subject matter can be modified by utilizing particular technologies (Koehler et al., 2013). TCK is used to further understand of a topic. Using the previous golf analogy, students could use a recording device such as an iPhone or iPad using interactive software to review their backswing, impact position, and follow-through. TPK “is an understanding of how teaching and learning can change when particular technologies are used in particular ways” (Koehler et al., 2013, p. 16). For the teacher, this means how to best choose and manage the technology selection for students and implies that TK and PK are effectively used together (Common Sense Education, 2016; Crompton, 2016). Continuing with the golfing example, a student could utilize software such as Hudl Technique Golf to evaluate and improve their golf swing. The student can document and share their findings while seeking feedback about their backswing, impact position, and follow-through from peers and experts in the field. WRAPPING UP 21st-century skills such as creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, and communication are actively engaged in this TPK example. The use of technology facilitates additional feedback for students that were previously unavailable. The delivery of 21st-century skills, such as communication, is inserted when using the TPACK framework at the lesson design phase. As teachers design lessons, they should determine what type of communication the students will develop and use, such as oral, written, or visual, and think about assessing the communication in their work. In the above golf example, the audience would include a community of golfers, amateurs, and experts, who, in addition to the teacher, could provide an assessment and feedback for the student’s progress (Dilley et al., 2015). In conclusion, TPACK reminds teachers to focus on content and pedagogy first and technology second. TPACK provides a framework for successfully integrating 21st-century skills and technology in the classroom (Common Sense Education, 2018; Crompton, 2016; Sheninger, 2016). TPACK additionally provides a framework to ensure the ISTE Standards are the outcome for effective classroom technology integration. The TPACK framework should guide teachers to effectively design and facilitate a lesson that integrates technology to promote high levels of student learning. Below are the resources mentioned from today’s post should you want to learn more about the successful integration of technology. In the meantime let us know how you are partnering in learning with your students in the comments below. If you found this post useful please join our Pedagogize It community and subscribe for free strategies for how to best use technology for learning. The Pedagogize It community revolves around what matters most, and that is you and the work that you do.

References:

Written last spring, Dr. DeWitt examined six themes he found during the pandemic and challenged his audience by asking what they want to take that worked well during the closure into a hybrid learning environment this fall. No surprise here, the student-teacher relationship still remains the linchpin in getting this to work. What I did find interesting was his message about the amount of control a teacher has over student engagement while teaching in the classroom and how this looks different when teaching in the virtual environment. Remember when blending, as the designer and facilitator for learning, we want to actively engage our students online and offline while offering students different degrees of control over time, place, pace, and/or path (Tucker, 2020). See the full article here. @PeterMDeWitt, #edtechchat, #edtech, #edchat, #blendedlearning  "If tech doesn't improve what we're doing, we shouldn't be using it" (Tucker, 2015). "If tech doesn't improve what we're doing, we shouldn't be using it" (Tucker, 2015). When talking to teachers about blended learning I have found general agreement about the foundational ingredients to blended learning. Ingredients such as giving students control of their learning by allowing them to learn at their own pace, place, and path doesn’t seem to scare away educators. Factors such as placing the student at the center of the learning experience brings no stop to the conversation, in fact, I found this to bring excitement to the dialogue. Instructors seem open-minded to relinquishing elements of control to the student, progressing towards a facilitator and partner in learning as the ISTE Standards for Educators suggest. Staff members are even willing to build upon their technological and pedagogical knowledge, and I couldn’t be happier.  Blending your learning can save you time, money, and increase one-on-one interactions with your students (Tucker, 2012). Blending your learning can save you time, money, and increase one-on-one interactions with your students (Tucker, 2012). There are a few ingredients however that I found curb the excitement and possibilities to blended learning, similar to how one turns the speed dial on the blender to the slow, if not off position. These ingredients are: (a) the high stakes assessment such as the end of course assessment, or more familiar traditional end of year state assessment; (b) an assumption that teachers have to teach their content in the same manner that they always have, replicating their face-to-face classroom in an online environment; and (c) that teachers must follow a highly regimented sequence of learning because of how their content area or subject matter builds upon itself. While the assessment additives are important to our fusion for learning, I don’t believe they are strong enough on their own to slow down or shut off the blender, albeit, some of these ingredients do bring required nutritional and educational value to our learning smoothie. So what should we do? Let a few questionable ingredients prevent us from making our learning smoothie? I don’t think so...I say blend them together. Look past the obvious and challenge yourself not to get stuck on foul-smelling ingredients such as assumptions and high-stakes assessments that limit you and your students from the many possibilities that a blended environment brings.  Kale, the distinct taste of high-stakes assessments. Kale, the distinct taste of high-stakes assessments. For those of us with more of a bland educational palate, we can always camouflage the kale and spinach high stakes assessment aftertaste by adding blueberries, mangoes, and orange juice to the mix...ultimately creating a fruity smoothie with the delectable taste of knowledge and the flavorful reward of applied skills. To learn more about going blended, including a thorough critique of this subject, watch this #silverliningforlearning YouTube episode led by a panel of experts including Dr. Catlin Tucker, one of the leading researchers and experts on this topic. Dr. Tucker can be found at catlintucker.com and I also invite you to explore the works of Scott McLeod, @mcleod; Yong Zhao, @yongzhaoed; and Punya Mishra, @punyamishra. If you found this post useful please join our Pedagogize It community and subscribe for free strategies for how to best use technology for learning. The Pedagogize It community revolves around what matters most, and that is you and the work that you do. Below are the resources included from this post if you want to learn more about successful integration of technology into your teaching.

When used appropriately, technology can be used to personalize learning and give students more choice over what and how they learn, and at what pace, ultimately preparing them to organize and direct their own learning. As an educator we can reference the ISTE Standards for Educators for ideas on how to best do this.

For example, in Designer Standard 5a, teachers should seek out how to incorporate student interests and curiosity as a means to the learning process, champion student voice and choice by using technology, and answer how technology may address and accommodate various learning needs. Use this time of remote learning to practice designing opportunities for students to create and manage their own personal learning goals, provide opportunities for students to take ownership of their own learning, and approach learning concepts from a new perspective. In his blog, George Couros has four ideas to consider for online learning that help teacher purposefully design “choice” into student learning. References:

Imagine being able to predict the success of your students, who wouldn’t want to be able to do that, right? Actions by teachers, called antecedents, may help make this dream a reality. Antecedents are “structures and conditions that precede, anticipate, or predict excellence in performance (White, 2005, p. 28). Like all lawyer television commercials this post comes with a disclaimer. There are no secrets in predicting student achievement in this post; only hypothesizing, heedfulness, and hard work will be introduced here. However, I will predict that we increase our chances of having a positive impact upon student achievement by having a better idea of the adult causes leading to the effects on student learning.  Antecedents are the actions of the adult, not the student. Antecedents are the actions of the adult, not the student. Antecedents can be categorized by “causes, instructional strategies, administrative structures, and conditions for learning” (White, 2005, p. 28). Antecedents are the cause for the effect in learning or goal attainment. These are the actions of the adult, and NOT the student. For example, an antecedent is not a student’s test score, however, the antecedents (practices) of the instructor leading up to the test result could (and should) be measured and monitored. Antecedents are also:

Consider this, if the adult is the cause, then the student’s learning is the effect. Identifying and monitoring antecedents are crucial as teachers and administrators usually know the effect (results), however, don’t always know or seek out the cause. Now that we know what antecedents are, let’s recategorize them into more teacher friendly categories of: teacher routines (causes), instructional strategies, and learning conditions (antecedents).  What teacher routines, instructional strategies, and learning conditions do you monitor? What teacher routines, instructional strategies, and learning conditions do you monitor? Think of teacher routines as classroom management. These are teacher behaviors that affect student achievement, no special training is needed, and can be replicated. For example teaching classroom procedures and establishing/following through on rules. Instructional strategies are the tools and practices used to help how we teach. These are teacher practices that engage students in thinking, require professional development and practice to do with fidelity (White, 2005). Examples of effective instructional strategies are response to intervention, cognitive task analysis, jigsaw method, and scaffolding (Hattie, 2017). Finally, learning conditions create the classroom environment. They are the actions that precede, anticipate, or predict excellence in performance and can be replicated. Examples include the posting of learning goals, excellent work displayed in the classroom, teacher explaining expectations to parents, and teachers making personal connections with students. You might be wondering, what does this look like in my classroom? Here is an example of a digital classroom categorized by the antecedents addressing a SMART goal.

This table outlines the adult actions taken that correspond to the identified weaknesses and to the SMART goal(s) (Magana & Marzano, 2014; White, 2005). The idea we are going for here is to envision what success looks like, but also identify the causal factors (antecedents) that contribute to the success. This is done by focusing on a few, high leverage antecedents for improvement such as using instructional strategies greater than the 40% effect size as identified by Hattie (just make sure the routine, strategy, or condition fits your desired context of learning). We need to know the cause for the effect on learning in order to be successful. Defining and monitoring antecedents is the first step towards data triangulation, which also includes accountability and collaboration.  Monitoring antecedents helps keep learning on target. Monitoring antecedents helps keep learning on target. The use and monitoring of antecedents in an accountability system is critical for student success. In a separate post I reference a continuous improvement accountability system that includes measuring and monitoring antecedents. Whatever accountability system you choose, White (2005) suggests to “ensure that action follows analysis; that roles and responsibilities are assigned to individuals and to teams; that user-friendly timelines for data management are established; and that accountability is integrated into every data-driven decision” (pp. 29-30). Note that Reeves (2011) advises collecting data around achievement data as specified in the school improvement plan. Other accountability data to monitor includes the number of data walls, students tracking their own progress, number of walk-throughs, and frequency of feedback from administrator to teacher to student to name a few (Hedgpeth, 2015). Just make sure the data collection measures are aligned back to the antecedent being monitored. The table below offers suggestions of what, when, and how to measure for accountability in a digital classroom, on the assumption of a 4C goal example of trying to increase creativity in the classroom.

Examples of ongoing and interim measures while making adjustments as necessary. Note that it is important to “name” the data collection tools and build capacity in each so teachers and leaders know what to look for and how to best provide feedback. Limit data collection tools to avoid collecting more data than necessary. Triangulating antecedent data with accountability measures is completed by including collaboration to the mix. Collaboration works best in the building and district when it is “(a) built into every step of data management, (b) applied in a culture of no blame and no excuses, and, (c) unified into every data-driven decision” (White, 2005, p. 30).  Data triangulation consists of having a time and place to collaborate, antecedent data to review, and an accountability system for continuous improvement. Data triangulation consists of having a time and place to collaborate, antecedent data to review, and an accountability system for continuous improvement. In summary, antecedents are the cause for the effect and challenge us to take on the role of the researcher. As the researcher we constantly seek to answer if the cause is having the intended effect on learning. We categorize antecedents by teacher routines, instructional strategies, and learning conditions. Instructional strategies are unique to this group as they require professional development and practice by the adult. Combining antecedents with accountability and collaboration makes for the most effective use of data triangulation. Predicting student success may seem like wishful thinking. I know we can’t control everything, however, I do believe we get what we create or allow (Cloud, 2013). Naming and claiming antecedents while triangulating accountability measures through collaboration is sure to create a recipe for student achievement success, just like we predicted earlier. Below are the resources mentioned from today’s post should you want to learn more about the cause(s) leading to the effect(s) upon learning. In the meantime let us know which antecedents you are monitoring in your classroom in the comments below. If you found this post useful please join our Pedagogize It community and subscribe for free strategies for how to best use technology for learning. The Pedagogize It community revolves around what matters most, and that is you and the work that you do.

Prensky (2010) recommended partnering with students and defined partnering as the way of working together to produce and ensure student learning in the 21st century. Partnering includes the roles of the teacher as coach and guide, goal setter and questioner, learning designer, control shifter, context provider, and rigor provider. He later added to the definition by saying that the teacher’s goal of partnering is not to tell (the answer), and here is how it works.  How do you plan for the effective use of technology in your lesson design? How do you plan for the effective use of technology in your lesson design? LEARNING TOGETHER In the partnering pedagogy, Prensky stated that it is the job of the student to use technology as the teacher coaches and models the use of technology for effective learning. For this to occur Prensky recommended teachers focus on things they already do but develop a deeper level of expertise in questioning, rigor, and feedback for students. This begs the question, what and how should I integrate technology into my teaching? Determining how technology will allow students to arrive at learning outcomes during the design phase of the lesson should guide planning. Fullan (2013) emphasized that technology and pedagogy should revolve around the roles of both students and teachers, while Sheninger (2016) iterated that students must always be at the center of the process when using technology for learning. Tamim, Bernard, Borokhovski, Abrami, and Schmid (2011) found that technology integration has the best effect when it is used to support student learning in the outcome rather than being used as a method for direct instruction. Determining how technology will allow students to arrive at learning outcomes during the design phase of the lesson should guide planning. Focusing on pedagogy first and technology second will ensure effective technology implementation (Sheninger, 2016) and allow your students to appropriately utilize technology to demonstrate their knowledge and skills to a local and global audience.  Are your students at the center of the learning process when using technology for learning? Are your students at the center of the learning process when using technology for learning? USING TECHNOLOGY TO DEMONSTRATE LEARNING Tamim et al. (as cited in Lee et al., 2013) found that technology was best used for basic skills and factual learning, a necessary step for students to be able to use technology at a deeper level such as demonstrating their knowledge by creation of projects. The authors argued that the cognitive outcome identified, project-based learning, produced the highest effect in learning because it helped learners to see the part/whole relationship, and it inspired students to locate information, seek out facts, modify findings, and collaboratively work with their peers. Student cognitive outcomes can be increased by having students (a) collaborate in small or paired groups with computers, (b) develop instructional elements that are sense-making in context, and (c) and build student basic skills and help them see the interconnectedness of subject knowledge in a project-based learning (Lee et al., 2013, p. 140). For example, as the designer of instruction your practices might include:

Challenge your students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills by incorporating technology into the outcome. Challenge your students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills by incorporating technology into the outcome. In conclusion, technology integration should be based upon student outcomes while keeping the focus of teaching to the verb. Research suggests placing an emphasis on what students can do with their knowledge, aligning teacher pedagogies with collaborative projects that spark the interest of the students, and moving the teacher away from the role of the knowledge expert to a facilitator who partners in learning with the students as successful ways to integrate technology in the classroom. Below are the resources mentioned from today’s post should you want to learn more about the successful integration of technology. In the meantime let us know how you are partnering in learning with your students in the comments below. If you found this post useful please join our Pedagogize It community and subscribe for free strategies for how to best use technology for learning. The Pedagogize It community revolves around what matters most, and that is you and the work that you do.

Getting started with integrating technology in the classroom can be a little overwhelming, however, the good news is that it doesn’t have to be and a good start is to know when to use it, or not. In his Classroom Q&A audio podcast, Larry Ferlazzo interviewed two instructional coaches and an elementary principal and asked for their perspectives on integrating technology into the classroom. Three great questions with a trove of knowledge is packed into this short nine minute interview, here’s the gist (responses summarized):  Students learn when technology is used to enhance and support good teaching practices, and learning is hampered when technology is used with ineffective instructional strategies (Magana & Marzano, 2014). Students learn when technology is used to enhance and support good teaching practices, and learning is hampered when technology is used with ineffective instructional strategies (Magana & Marzano, 2014). When asked “what is one important criteria teachers should keep in mind when deciding if they should use tech in a lesson and why?” (Ferlazzo, 2019).

Reflecting on “what is a common mistake made by teachers using tech in the classroom?” (Ferlazzo, 2019).

And finally, when asked “what is one simple thing teachers can do to add value to their lesson?” (Ferlazzo, 2019).

WHAT RESEARCH SAYS These expert responses align with research and best practices for the effective use of technology in the classroom. Students should also have a sense of the digital tools available to them and know which tool best fits the need for the desired outcome. Wadmany and Kliachko (2014) identified technology contributions and recommended classroom practices. Findings included that technology increases flexibility in learning, demonstrates learning, allows for collaborative learning, differentiates and personalizes teaching and reduces learning gaps, and allows for learning to carry on beyond the school walls. It is not what technology is used, but how it is used that counts for student learning. NO GUARANTEE Adding technology into the classroom does not guarantee an increase in student achievement. Using technology to supplant teachers or to make up for ineffective practices almost guarantees poorer outcomes in achievement. Teachers should heed the notion that it is not what (technology) is used, but how it is used that counts for student learning. More importantly, a review of how students and teachers benefit from using technology to develop knowledge and skills is warranted while recognizing that successful integration is aligned to changes in teacher practices, curriculum, and assessments (Mohammed, 2018; Vega, 2016).  Successful integration is aligned to changes in teacher practices, curriculum, and assessments. Successful integration is aligned to changes in teacher practices, curriculum, and assessments. THE LAST WORD In summary, technology integration should be based upon student outcomes while keeping the focus of teaching on the verb. Research suggests placing an emphasis on what students can do with their knowledge, aligning teacher pedagogies with collaborative projects that spark the interest of the students, and moving the teacher away from the role of the knowledge expert to a facilitator who partners in learning with the students as successful ways to integrate technology in the classroom. Given these points, successful integration of teaching with technology is more than possible. Students learn when technology is used to enhance and support good teaching practices, and learning is hampered when technology is used with ineffective instructional strategies (Magana & Marzano, 2014). Below are the resources mentioned from today’s post should you want to learn more about the successful integration of technology. In the meantime let us know your responses to the three Classroom Q&A questions from above in the comments below. If you found this post useful please join our Pedagogize It community and subscribe for free strategies for how to best use technology for learning. The Pedagogize It community revolves around what matters most, and that is you and the work that you do.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed